Kudakwashe P Vanyoro, Leila Hadj-Abdou and Helen Dempster share their agenda for bringing about change in the increasingly important field of migration studies

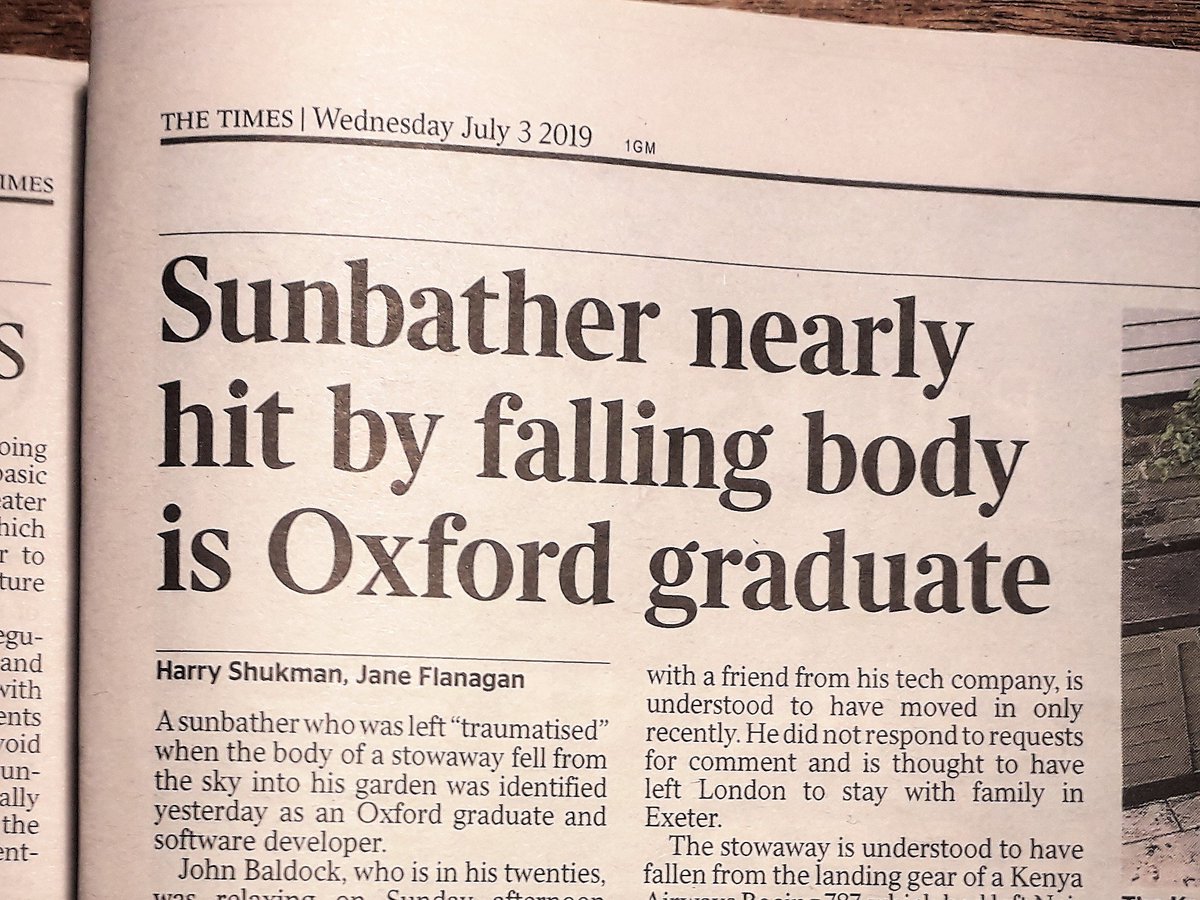

Last week, an African man died in a London garden. He fell from a Kenya Airways flight, as the landing gear opened over Heathrow Airport. News reports highlighted the horror as he landed a metre from a sunbather with witnesses expressing sympathy for those who came across the body. The image’s caption describes how the force of his ‘frozen’ body ‘dented’ paving slabs.

Headline from The Times, London/@johnkiszely

Headline from The Times, London/@johnkiszely

Why was the ‘gaze of sympathy’ focused on the discomfort experienced by the sunbather, an Oxford graduate as the papers emphasised? Where was the focus on the African man? Why did he do what he did? Who was he? Why has this tragic death resulted in condolences and not more proactive action? These questions all point to broader discussions about the dehumanising of migrants. This dehumanisation comes with a price. Research has shown that it deactivates social cognition processes in human brains, which spurs extreme violence towards groups when viewed through such a lens.

What can (and should) migration academics and practitioners do to engage in these discussions in a meaningful way? To address this question, we coordinated a participant-led session at the 15th Migration Summer School held at the European University Institute’s Migration Policy Centre. The Summer School brought together academics and practitioners working in various policy and humanitarian institutions around the world. We used this opportunity to create a constructive and safe space for debate, discussion and to foster critical reflection on this question.

Delegates at the Decolonising Migration workshop at the 15th Migration Summer School in Florence

Delegates at the Decolonising Migration workshop at the 15th Migration Summer School in Florence

In this short piece, we summarise these reflections and existing literature on decolonisation to outline what a shared, productive, decolonial agenda for migration research, teaching and practice could look like. Perhaps it is here, where the current racialised dehumanisation of (some types of) migrants, and their possible emancipation, are located.

Why decolonisation is a useful lens

During our session, we argued that decolonisation has an inclusive, open-ended definition. For academics and practitioners, it concerns a reflexive exercise – imagining what a freer, less hierarchical world could look like. Such a world is certainly not one where African migrants desperately stow away in planes. Decolonisation allows us to deconstruct the moral legitimacy and racialisation of these actions.

But we cannot understand the dehumanisation of certain ‘migrant subjects’ without a reference to the continuity of colonialism, manifested in current power asymmetries between and within different world regions in the Global North and South. We felt it was important to go beyond colonialism as a particular moment in history, to confronting coloniality as a concept that refers to long-standing patterns of power. These patterns define culture, labour, intersubjective relations and knowledge production, well beyond the formal ending of colonial rule. We found this replicated itself in two ways: in our positionality within institutions; and in the categories we use.

Understanding our own positionality

All of us working in migration research, teaching and practice need to acknowledge the possible influence of our different ethnic, professional, racial and gendered positions, and assume responsibility for this. In particular, what are the real-world consequences of our multiple biases, decisions and actions for the broader experiences of migrants? How are unequal power relations reproduced in our work? We have to bring these discussions into our work and into our classrooms. Debates about cognitive biases and positionality should not be contained to disciplines such as social psychology, but have to be part of broader discussions in higher education and academia. This also implies that researchers have to see themselves as part of (in our case) migration governance systems. Scholars do not simply speak truth to power; but are part of these power constellations by making sense of the world in a certain way and by producing knowledge that is always shaped and formed in a context of power. We have to take into account what the scholar Achille Mbembe and others have coined as ‘epistemic coloniality’ referring to processes of knowing about ‘others’ but never fully acknowledging these ‘others.’ The way that we approach migration research and practice is inherently coming from a position of power – since we conduct research on the other.

A paradigmatic example we discussed from our field of studies is migrant integration research – where we study the inability of the other to conform to society, not the ability of society to adapt and accept the other. Migration researchers have to create awareness among their peers and their students that while this type of research can have an inclusive value, it also tends to be a tool of boundary-making. The integration concept ignores the fact that social differences are constitutive of the social, and that the idea of immigrant integration often tends to perpetuate a line between those for whom integration is not an issue at all and those who are in need of integration.

In some sense it also means re-politicising what has been depoliticised. The notion that we need to rely more on empirical evidence sounds reasonable and valuable in this post-truth era. The difficulty in achieving this implies a tendency to avoid debate and honest dialogue. Hence, we have to come up with ways to overcome echo chambers and polarisation. These skills should be incorporated into the syllabus of migration studies (and other) programmes. In order to open up space for debate and emancipation, we however also need to create trust and an environment of feeling safe to reflect and act on errors. Training and teaching in higher education should incorporate this principle (see the section titled Theory to practice: what lessons can we apply to our teaching?)

The many faces of migration/mobility: Was MK Gandhi an international student, economic migrant, victim of colonialism, or human rights hero?/© Robin Sones (cc-by-sa/2.0) *

The many faces of migration/mobility: Was MK Gandhi an international student, economic migrant, victim of colonialism, or human rights hero?/© Robin Sones (cc-by-sa/2.0) *

The most interesting part of our discussion was our reflection on whether working in ‘rigged’ spaces is the problem. Many felt they were severely bounded by bureaucratic and institutional constraints of working in environments where they were constantly required to toe the line and subscribe to politically correct ideologies. We thus need to reflect on institutional constraints and the importance of public opinion. In spite of these realities, we emphasised the need to position ourselves as powerful actors who could contribute negatively or positively to the realisation of rights and dignity for human beings through our actions.

We also spoke about our ineptitude to reflect on what we thought about our work as academics and practitioners, and the potential of this blindness to contribute to the reinforcement of the status quo of racialising migrant bodies through containment, detention and death. Even working within a ‘rigged’ space, speaking off-the-record and personally challenging some of the approaches taken by these institutions was embraced and encouraged as exercises in decolonisation, for the coloniality of power lies in always assuming that we are right without interrogating our own actions as individuals.

For higher education, a good way forward would be to consider that while organisations tend to be change-averse and to reproduce dominant perspectives; when differences in a group rise above 30 percent, new ideas and approaches filter through. This means not only considering hiring staff from different social backgrounds, but also from different-sub-disciplines and academic cultures that subscribe to and endorse different ways of thinking. Academic careers are still made by sticking to narrow sub-disciplines; interdisciplinarity, while officially praised, is often punished. This approach could also factor in research evaluations. Having a broader view on the necessity of difference and a higher threshold in academic hiring also would avoid tokenistic measures.

The coloniality of the categories we use

As noted above, we were struck by some of the potential dangers of concepts such as integration in the ‘othering’ of migrants, which ultimately can be used to justify their dehumanisation. We drew on existing critiques of the relationship between immigrant integration as a social construction and the specific ways in which it is applied to the level of the individual to ‘purify and immunise a preconceived society’. Such issues also come through when discussing categories of refugee, migrant and asylum seeker. On one hand, these categories can be useful and are used to provide access to rights and services; but on the other hand, they can also reinforce strict lines between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ immigrants, only some of whom are deserving of our protection. This reproduces the exclusion of certain migrants and their constitution as ‘out of place.’ In teaching and research we repeat these dichotomies, as migration research tends to maintain a pro-migration inclination. Instead, we might want to focus on larger questions of inequality both for migrants and non-migrants, including the hierarchies and stratification among different types of ‘migrants.’ This to some extent also requires the de-migranticisation of migration research.

Another issue is the portrayal of migrants either as victims or heroes. While practitioners and migrant advocates see this as helpful, we should emphasise in our studies and in teaching that it is not the case. It obscures the view of migrants as ordinary people – people one can identify with – and instead portrays migrants as either tragic or miserable, or as the exemplary citizen.

Syrian migrants' life jackets on a beach/romaniamissions *

Syrian migrants' life jackets on a beach/romaniamissions *

The body count in the Mediterranean and the graphic visualisation of dead migrant bodies are examples of this to which many migration scholars have contributed. While no death should be forgotten, and deaths can serve as a powerful reminder of colonial legacies, this way of speaking and thinking of migration also disrespects brown bodies and creates a border porn spectacle that reinforces rather than alleviates the inequalities and processes of racialisation. As many of our students will go on to work in organisations such as the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or migrant advocacy non-governmental organisations (NGOs), fostering awareness that both the ‘bad’ and ‘good’ migrant narratives are problematic is crucial.

We also explored the potential utility of applying a mobility rather than a migration lens, moving away from a lens through which migrants are currently constituted as a problem to be dealt with. A mobility lens is broader, allowing movement to be seen as a fundamental aspect of social life. A focus on mobility helps to overcome the sedentary bias of social sciences and can effectively challenge methodological nationalism.

Finally, we emphasised the need for reflection – constantly considering how our positionality impacts on our decisions and actions, no matter what spaces we work in. A colleague working in the United Nations gave a practical example. In seminars, staff deliberately tackle sensitive issues in order to develop empathy for different positioning; whereas in higher education today, we too often avoid sensitive issues. This type of political correctness has resulted in a political backlash rather than overcoming it. To move forward, we have to learn how to engage in a productive way with each other. These processes have to be supported through schemes and mediation techniques.

Obviously these actions are not going to be enough to fully overcome the coloniality of the structures in which we live and work, nor will they fully humanise migrants, but they are a start. Migration research has initiated this importantreflexive turn; this conversation has to continue.

Note: The authors do not represent the position of their respective institutions, but express personal views in order to stimulate an open debate. The order of the authorship reflects that it was the initiative of Kudakwashe Vanyoro to have a session on decolonisation within the MPC Summer School, Leila Hadj-Abdou organised the session, and Helen Dempster and Kudakwashe Vanyoro came up with the idea to write this blog. All three authors have equally contributed to this blog.

Image information:

Main Image: Sky News

The many faces of migration and mobility: cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Robin Sones – geograph.org.uk/p/5791568

Syrian lifejackets: romaniamissions

Theory to practice: what lessons can we apply to our teaching?

Dichotomous thinking

Immigrant-citizen, victim-hero are binaries that engender a simplistic understanding of migration and immigration through a migration lens. As the authors have suggested, a mobility lens that encompasses vagrancy, migration, transience, global and national poor, etc. may be more useful. Using diverse vocabulary that acknowledges the historical origins and socio-political context will enable your students to develop a more nuanced appreciation of the issue. View this short clip, where Bridget Anderson discusses the issue and the terminology.

Border porn spectacle

In this article about the tragic journey and death of an infant Salvadoran girl and her father, Tina Vasquez questions whether it is acceptable to use this family tragedy as political fodder. This view applies to our teaching as well. When we discuss human movement and migration with our students, are the migrants props in our narrative or do we create space for them to tell their own stories and explain the issues from their perspective? The authors make the same point about the media coverage of the stowaway’s deathly fall from a Kenya Airways flight at the beginning of this post.

“A travelling paradox”

Ngugi wa Thiongo narrates an anecdote that gives us a glimpse into what it means to be a Global Southerner travelling the Global North:

“Exile is more than separation: it is longing for home, exaggerating its virtues with every encounter with inconvenience. It’s worse for a third-world passport holder in the west, where one becomes a travelling paradox. … Three years ago my 17-year-old son, Thiongo Kimathi, and I went to Berlin for the celebration of the German translation of my novel Wizard of the Crow. His American passport got him through without a question. My Kenyan passport had me stopped and questioned. My son intervened with all the authority of his American accent and passport. The official looked at me suspiciously as if I had kidnapped the American boy, flung my Kenyan passport at me, and warned me not to stay one hour beyond the three days prescribed in the visa. I would be treated as an illegal immigrant.”

When discussing global travel, are we mindful of whether we and our students might see it as entitlement, harmless tourism or a nightmare? What assumptions do we make? How does this shape the ensuing discussion?

Lee-Ann Sequeira

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

3 Comments